| ch. 4, pp. 36 - 39 |

A comprehensive approach to flood management may encompass physical structures to protect bridges and other facilities, programs and ordinances to regulate the use of floodplains and purchases of flood prone land. Structural Strategies

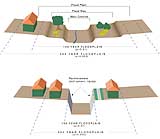

A structural approach consists of physical modifications to adjust and change the flow of floodwaters. For example, stormwater often was considered best managed and controlled if made to flow expeditiously from an area. Structural methods were adopted to widen, straighten and channelize waterways in efforts to reduce damage. Structural methods included such measures as levees, channel stabilization and storage reservoirs. These methods often were applied to prevent bank erosion, Tucson’s priority flood damage problem. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, vegetation was often removed from channels that would then usually be straightened and coated with concrete. This was done to quickly direct water from an area. Examples of this approach can be seen at Kino Boulevard south of Broadway and at 12thth Avenue south of I-10. This operation protects the immediate area, but is liable to increase the rate of flow downstream, causing greater downstream damage. Channels subject to this procedure are not suitable recharge sites. Starting in the 1970s, Pima County adopted a new technique and stabilized river banks with soil cement along the Santa Cruz River and Rillito Creek. (See Figure 4-5.) Soil cement is made from a mixture of cement and river soil and is applied to the banks of a channel. In some areas, large rocks are held in place along banks with wire meshing, to stabilize the banks. Called rip-rap, this construction needs regular maintenance to prevent it from deteriorating and being washed away. Both of these methods allow for recharge in the channel bottom, but not along the previous floodplain. Such structural methods for controlling floods may successfully resolve a local concern but may result in other flood-related problems downstream. For example, with bank stabilization in place, erosion may be controlled and even eliminated along a stretch of a waterway. More runoff, however, then flows downstream with greater force, resulting in increased erosion of banks and, therefore, greater downstream flood damage. Also, the force of the water flow may move the site of natural recharge to downstream areas where it may not benefit major wells. Nonstructural Measures As the result of above-mentioned concerns — many of which are now the focus of political debate — flood control strategies that rely on nonstructural methods have grown in importance. Such methods avoid physical modifications of the environment and instead maintain the natural conditions of river channels. Nonstructural measures generally encourage society to adapt to natural flood conditions when occupying or modifying a floodplain.

Floodplain management is the full range of codes, ordinances and other regulations adopted for minimizing flood damage, including zoning codes, building codes and subdivision regulations that may either prohibit construction in flood-prone areas or allow some construction under certain conditions. Floodplain regulations also may be enacted to prevent consumer fraud by requiring disclosure of possible flood hazards. It can also include flood forecasting, information and education, disaster preparedness and assistance, warning systems, evacuation, flood insurance and floodproofing. Arizona law requires cities and counties to have flood management programs. Both Tucson and Pima County, however, go further than the state requires and have ordinances to encourage leaving floodplains as natural as possible, including the use of native vegetation. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) requires communities to adopt approved floodplain maps and to regulate use of the identified floodplains for residents to qualify for flood insurance. EPA requires management of urban stormwater to minimize pollution, and both Tucson and Pima County have approved stormwater management plans. A full discussion of these requirements is beyond the scope of this report, although some additional information is contained in Chapter 7. Floodplain Acquisition

Since the 1980s Pima County has actively acquired flood-prone lands to keep them from being developed in order to minimize downstream flood problems and reduce flood rescue costs. These areas can then be used for open space recreation and wildlife habitat. Cienega Creek, a perennial stream south of Saguaro National Park East, is a prime example of this approach. Pima County owns a portion, and most of the upstream area is also public land under ownership of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service. Tucson and Pima County also have acquired flood-prone lands and developed linear parks, often in cooperation. Much of the land along the Santa Cruz River, both upstream and downstream of the downtown area, is now in public ownership and used as a linear park. The City of Tucson’s Multiple Benefit Water Projects propose ways of using CAP water to develop areas along the Santa Cruz River for wildlife habitat and recreational purposes. Tucson’s Stormwater Master Plan A watershed is a geographic area defined by the flow and movement of surface water, with all flow feeding one watercourse. The Colorado River watershed is made of many smaller watersheds, including the Gila River watershed, which in turn is made up of many smaller ones, including the Santa Cruz River watershed. Encompassing the flow of runoff within an area, a watershed is a hydrologically appropriate unit to determine the management of stormwater. Without such an approach, land use policies upstream may not be coordinated with the principles for managing stormwater runoff downstream.

|