|

|

|

|

Welcome to the IERE Agricultural Environmental Management Program.

The program is based on international voluntary standards for

environmental management (the ISO 14000 series) and has three

components:

Each element can stand on its own feet, but together they make a complete community based program.

ISO 14000 is a series of international consensus standards on environmental management. They lay out the way for any enterprise to manage its environmental impacts, and move towards sustainable practices. The primary document is the ISO 14001 standard, which bases environmental management on a continuous improvement approach, following the plan-do-check-act cycle. The idea is to make a plan, follow it, check to see how it is working, and based on that checking, act to make further improvements. This approach allows everyone to bite off the piece that fits in their mouths-- eventually eating the entire elephant.

Our program uses Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as the measuring stick for measuring environmental performance. LCA is a science-based way to measure environmental performance of goods and services. It looks at all the environmental impacts of a product from cradle to grave, based on the useful function that that product provides. That means, for example, that the impacts of the resource production and manufacture, packaging, distribution and disposal are all included in the assessment. Doing a life cycle assessment takes time and requires a great deal of data, so our program steps people into the measuring system a bit at a time. Standards on doing an LCA are part of the ISO 14000 series.

The first step is to develop a farm-based environmental management system (EMS for short). This describes how you operate your farm, field by field, and how you are working to make it more environmentally friendly. We have some forms and examples that will take you through this process step by step. You do have to write down the elements of your EMS.

What drives your EMS is your annual farm plan. This is a description, field by field, of how you will manage your farm to reduce environmental impacts. But there are some other details that need to be taken care of first.

Your farm EMS starts with your environmental policy statement policy statement. A policy statement tells the world what you think about the environment, and what you want to do about it. You should be able to paste your policy on the wall, and be able to look at it when you have forgotten why you are doing all this environmental stuff, and say, "Yes, that's why!" Everyone on your farm should know what the policy is-- you should discuss it around the dinner table to make sure that your spouse and kids know about it, and can see why you are doing what you are doing.

Even better, you should involve your family and any employees in writing the policy statement, so that it really reflects everyone's feelings and aspirations for environmentally friendly farming. The policy statement says what your aspirations are, and how you plan to get there. Somewhere in your policy statement, you need to commit to three things:

Your policy statement can be as long or as short as you like, but it should be something you can live with and be happy with for many years.

Here is an example environmental policy statement:

Jack's Farm tries to grow the best vegetables in the world, and being environmentally the best is part of being world's best. We want our farm to be completely sustainable. To do that we make an annual plan that everyone on the farm is responsible for knowing and following. Not only do we comply with all the regulations, but every year our plan makes us a little better environmentally. By polluting less, and by conserving our natural resources, we will make our vegetables a source of health and pleasure to our customers, and our farm will be a safe and healthy place for generations to come.

Here is another one:

The Blue Ribbon Dairy is an organic dairy, but we want to go beyond being organic to make milk products that fully protect our environment, going well beyond compliance. We want to decrease all the impacts of our products on and off farm, too. We follow the IERE program that uses life cycle assessment to measure these impacts. This helps us work with our suppliers to reduce pollution and conserve resources, getting a bit better all the time.

Your policy statement should be what makes sense to you!

Mechanics the EMS

The environmental management system is what you are doing to protect the environment. The ISO 14000 standards tell you what you need to document to be sure that you have systems in place to accomplish your goals. The documentation should help you do what is necessary to protect the environment.

You will have to write down your EMS and farm plan, describing how you will get to your goals and objectives, and you will also have to keep records of your farm activities. There are also a few other things to document. These are important to protect the environment and to meet the requirements of the ISO standards. Your written EMS is a permanent document, although checking it out for accuracy form time to time is a good idea. Your farm plan changes every year, as you change what and how you are farming. The annual report is just what it says-- annual.

This may seem like a lot of paperwork, but in fact, we have streamlined it as much as possible and farmers that have worked with us on their EMSs uniformly say that the discipline of getting the data and records together has helped them to understand their farms better.

Compliance on a farm varies significantly depending on how you farm and where you are. You should know the environmental laws and regulations you need to follow on your farm. Some of these may be federal, some state, and some local regulations. The most common ones are

There may be other regulations you need to know about-- find out by calling your local state environmental regulators and your cooperative extension agents. Keep a copy of any regulations that you need to follow, and keep any record they require.

Keeping Records should not be a complicated thing. You may keep your records in a pocket calendar that you carry with you as you go about your work on the farm. This is what we recommend if you have a small farm. Or you may be relying on the contractors that do things like applying your pesticides. You may be putting your records into a book in the milking barn. Regardless of how you keep your records on a day-to-day basis, remember from time to time to put that information into a file of what you did for that field. This has to happen at least once a year, and on a small farm this may well be enough. If you are managing a larger property, though, you may find it easier to organize your data more frequently: quarterly or even monthly. Your EMS should state how you are keeping records, and making sure they are being updated properly. Some of your records may be required by law, especially if you apply pesticides yourself.

Monitoring is all the day to day observations you make to keep track of the farm and tis environmental status. That means checking soil moisture, scouting for pests, tracking milk production and so forth. If you run a feedlot and have monitoring wells, monitoring includes the measurements you make in those wells. Monitoring data tells you when you have to make corrective actions.

Corrective Actions are mid-course adjustments during the year. This means you are thinking ahead to make sure that you meet your goals and objectives. For example, if you planned to reduce pesticide use by 50%, and you find you are close to the 25% before spring planting is over, you may want to change how you are doing things, to give yourself some room to use pesticides later during the year. Or if you planned to put in a fence to keep the cattle out of the wetlands, and it is November and you haven't ordered the fencing material yet, you can still get that fence ordered and installed before the end of the year. But even without making summary records, thinking about your environmental goals as you work around the farm, you will be able to see where you are off track and make corrective actions. Write them down when you make them.

Your EMS must state how you are going to perform monitoring and corrective actions. That means that you need to write down how you are checking things out. If you are doing a manual check of the soil moisture (seeing if it clumps) then you write that down. If you are using a soil moisture meter, write that down. The point is not to have the fanciest monitoring system, but to make sure that you have a way to monitor everything that matters.

Likewise, write down your corrective action decision points. That means that you should know the insect density that becomes a financial burden, so you know when to apply insecticides (if ever). Every state has an IPM specialist who can tell you what these decision points are.

Make a table of your monitoring methods and corrective action points.

Operational controls are the things you do to make sure you will maintain good environmental quality, and meet your improvement goals. Examples of operational controls are the way you manage your manure, and the use of monitoring for pesticide, fertilizer and water application. Another example of operational controls is use of low till or no-till methods.

Preparing for emergencies is an important part of environmental planning. What would happen to the environment if you suffered a tornado or earthquake or flood? Do you have manure lagoons that could overflow? Are you storing pesticides that could be distributed all over the county? Spend some time to think about what could happen to the farm in the event of a natural disaster, and what you should do if they happen. This should lead you to finding ways to make emergencies NOT happen. You need to write down your emergency plan.

Internal communications. If you have any employees (even if they are family members), you must keep them informed about your environmental plans. They need to know about your policy statement, and they need to know what they must do to help you meet your goals and objectives.

External Communications: The IERE plan requires that you write an annual report about your farm's environmental program. We post that report on our website. Every annual report has the following elements:

Auditing. This is one of the "checking" parts of the EMS. At least once a year, you need to go over your environmental performance: did you meet the goals you set yourself? Look at your corrective actions, to see if there is some pattern indicating that a particular system needs changing.

Ideally, you should have an outside person go over your records with you so that a fresh pair of eyes can see your opportunities for improvement. IERE will do a paperwork review of your farm. If funds are made available we can do an on-site review. This may be from one of our offices (in Seattle and in Davenport, IA), or it may be from IERE trained community environmental council members.

.

The farm plan has five steps:

At the end of the year, you will also have to evaluate your progress versus your goals and objectives.

Data Gathering

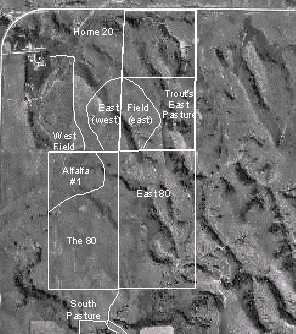

You manage your farm one field at a time. So you need to gather data about the activities of your farm one field at a time. The first step in developing your plan is to identify each field you have, where it is and some basic characteristics such as how large it is and whether it is irrigated. To do this you need a map of your farm, and mark each field's location.

Your cooperative extension agent can get you a map, or, if you are linked to the internet, you can get a satellite photo of your farm. Once you have a map, you need to mark off the fields. The map below is an example where this has been done.

Be careful in identifying your

fields. If you sometimes plant half of a field one way and the

other half another way, you really have two fields, and should

give them different names. Some people number their fields, and

that is OK, too. The key is to know what land you are talking

about, and have a unique identifier for every parcel that is managed

as a unit.

Be careful in identifying your

fields. If you sometimes plant half of a field one way and the

other half another way, you really have two fields, and should

give them different names. Some people number their fields, and

that is OK, too. The key is to know what land you are talking

about, and have a unique identifier for every parcel that is managed

as a unit.

The next step is to make a table of your fields, showing the activities for each field: what you grew on that field last year, and all the cultural practices you used.

The cultural practices include: how you tilled the soil (when and how and how often) how you fertilized the soil (when and with what and how much), how you used pesticides, if any (when what and how much), what you planted (what, when and how much), and how much you irrigated each field. Note how much fuel or electricity you used to manage each field.

Finally, figure out your yields from each field. If you are growing grain, this is easy. You should have records of bushels yield or tons sold. If you are raising animals it is a bit more complicated. You should note animal days of grazing as well as the marketable yield, such as hundredweight of milk produced or pounds of animal sold less pounds of animal bought. Finally, make one more table where you add up all the numbers to get an overall farm picture for the year: the inputs, and the production. In this last table you need to put in any on-farm processing, and any transportation of your crop.

The last set of data needed id the soil quality data. For each field. You should measure the following properties: Organic carbon, topsoil depth, nitrate + nitrite, TKN, Phosphate, and potassium. This information will help you decide whether and how to fertilize your fields, so the best time to measure them is before planting. It will also provide us the information we need to calculate the impacts of your farming practices.

Evaluating Aspects and Impacts

Now you have a record of what you did last year, and can start to understand what are the environmental aspects for your farm. Here is where you start thinking about your farm from an environmental perspective. You want to know and understand the environmental aspects of your farm that may cause environmental impacts, and know how they are linked to your farm activities, products or services.

Below is a list of the environmental aspects and potential impacts of farm activities.

|

|

|

|

| Tillage |

Burning fossil fuels Releasing carbon fixed in soil |

Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; soil erosion; destruction of habitat; fossil fuel depletion |

| Planting | Burning Fossil Fuels | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; fossil fuel depletion |

| Fertilizing | Use of nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfate and potassium; using fossil fuels | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; human health effects from groundwater; salinization of soils; destruction of soil microorganisms; fossil fuel depletion |

| Pesticide Application | Pesticide use and release; fossil fuel burning | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; human and ecosystem toxicity through pollution of air, water, groundwater and crops; fossil fuel depletion |

| Irrigation | Use of water; burning fossil fuels or using electricity | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; water resource depletion; salinization of soils; fossil fuel depletion |

| Cultivation |

Burning fossil fuels Releasing carbon fixed in soils |

Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; destruction of habitat; fossil fuel depletion |

| Harvesting | Burning fossil fuels; removal of fixed carbon | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; fossil fuel depletion |

| Processing | Burning fossil fuels or using electricity; possible use of water or freons | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; water resource depletion; stratospheric ozone depletion |

| Transport | Burning fossil fuels | Climate change; acidification; eutrophication; fossil fuel depletion |

You already have a list of your activities, and numbers on your environmental aspects: how much fuel you used, what pesticides you used and how much, and similar things. You need to take that list and decide which ones are important, and which ones are not.

Think about your environmental aspects two different ways to make this decision. First, is the impact important? The answer to this question depends on your values, and what you know about your local environment. For example, suppose you are looking at the aspect of water use, and you live in Arizona. You KNOW that water depletion (the impact of water use) is important. Fresh water is a very limited resource there. If you live in New England, water resources are abundant, and water resource depletion would be rated low. Rate each impact as high, medium or low. Global warming and stratospheric ozone depletion should both be rated high, because they are world-scale and long-term problems.

Second, ask whether the amount or size of the aspect is large. Are you using pesticides only on invasive species, and only using hand application? Then rate that aspect low. Are you only using water to water your stock (not irrigate the crop)? Then the water usage and this environmental aspect are low.

Once you have gone through the aspect and impact rating (high, medium or low), then look to where you have high-high ratings as the place where you might want to make some improvements. If you don't have any high-high ratings, then look at the medium-high or high-medium ratings as the opportunities to improve. Every aspect that you rate as high-high must have a plan for it. That means that you must be looking at ways to reduce its impacts. Sometimes there is no obvious "fix." You should still have a plan to get more information on the problem, or to keep track to new technologies or ideas.

When you have been managing your farm's environment for a year, we will be doing a life cycle assessment of your farm products. This will look at the environmental impacts of the products, evaluating not only on-farm activities, but also the things that happen off-farm (like transport and packaging). A life cycle assessment is the basis of the ecolabel that IERE provides. Once a life cycle assessment has been done, you will be using the impact indicators, rather than the environmental aspects to manage and measure your environmental performance.

Setting Goals and Objectives:

This is the part of the plan where you decide what you want to take on to improve the environmental performance of your farm. These are your goals and objectives for the year Using your ratings, pick out the things that you can do to improve your environmental performance in the next year.

You probably noticed that the environmental aspects can be described with relatively few items: burning fossil fuels; disturbing the soils to reduce fixed carbon; using fertilizers and pesticides and using water. You can make significant environmental improvements on the farm by employing just a few practices:

There are some more advanced techniques you can use, too, such as:

For example, you might decide to practice no-till farming in one field. Or you might want to overplant one pasture with native species. Or you might choose to hire an agricultural consultant to do your scouting for IPM. Pick out the ones that you can afford, and that you have the time to do. You want your plan to be successful! Even if you only pick out one thing to do, you will be making the environment better.

Regardless of your goals for the year, you need to write them down, and you need to gather data on what you did to meet that goal. Ultimately, you will be reporting how you did versus those goals, so it is a good idea to choose goals that are feasible with the resources you have at hand.

Reporting Progress: The Annual Report

Once a year, you will be preparing an annual environmental report, and we will post that report on our web-site. The goal of this report is to tell the world that you had a plan, and how you performed versus that plan. The elements of the annual report are:

Example annual reports can be found on our website www.iere.org/sustain/.

Ecolabels are the economic driver of IERE's program. Ecolabels for foods have been found to provide significant price advantage at retail, sometime as much as 200%, but 40% is more common. IERE's program is based on the ISO 14000 standards for ecolabels, and they are a Type III ecolabel. That means that they are based on a life cycle assessment of the product. We look at the environmental impacts of agricultural products in what we call a "cradle to plate" approach. On farm, that means that we look at the inputs and outputs of every field, and model all the impacts for which there are reliable models. Off farm, we model the impacts of the production of fertilizers and pesticides and fuels, the impacts of electricity production, and all transportation costs, as well as impacts from processing, packaging and refrigeration.

It is a lot of data collection, and we don't expect to have everyone have all the information for their ecolabels right away. What we do expect, is that the farmer provide all the relevant on-farm data within a year of joining our program. We will be using industry averages to estimate the off-farm environmental impacts. In subsequent years, we expect that some of the off-farm data will begin to be collected, so that we can model the specific impacts of the farm product.

The Impact categories we will be modeling include:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In addition, we will be reporting, but not modeling, the following information:

Regardless of the indicator, we will be reporting the result in comparison with the US average for that environmental category. This will permit interested parties and especially consumers to put the environmental efforts of the farm into perspective. No ecolabel will be provided for products that are not better than average on all environmental indicators.

Land Use and biodiversity is a special issue for ecolabels, in that there is no consensus about which indicators are best to measure this impact. Nevertheless, there is clear consensus that land use changes are the most important source of environmental degradation that derives from agricultural practices. We are working with a coalition of experts and interested parties on this issue, and until we reach consensus on the best indicators (a process which is expected to take years), we will be using the following indicators:

| Proposed Measures |

|

Acreage of habitat that is physically protected (i.e.; through fencing or other methods); habitat to be identified as including

|

| Acreage of habitat set aside (not farmed) that is identified as "high priority" in TNC vegetative maps |

| Total linear space of aquatic habitat (i.e. river, lakeshore, etc) protected via physical means vs. total area managed |

| For physically protected areas, density of non-native vegetation (area percent) |

| Miles of road per square mile |

| Acreage in native species dominated areas/total area managed |

| Acreage newly returned (in last 12 months) to native habitat |

| Number of Best Management Practices (i.e. operational control related to biodiversity) adopted |

|

Size of native-managed acres vs. total acres managed Size of native-managed acres vs. average field size |

| On managed acres, percent of native-managed land units that has at least one adjacency to other native-managed land |