| ch. 2, pp. 10 - 12 |

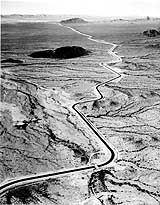

At the next regular election in 1978 controlled growth advocates were defeated in the Board of Supervisors and the Legislature, and the City Council approved Tucson’s CAP sub-contract. The sub-contract was for the entire metropolitan area, based on the assumption that the city system would continue to expand. The Council also approved water conservation programs, and Pete the Beak, cartoon star of the Beat the Peak program, was hatched. The program was originally designed to encourage landscape watering at non-peak hours, thereby delaying the need for expanding the system of water mains and reservoirs. The program, however, also had the effect of encouraging water conservation more generally. During the 1980s, the city increased its water conservation efforts, partly in response to the requirements of Arizona’s new Groundwater Management Act. Tucson had some of the lowest rates of per capita water consumption in Arizona because of these programs and the perceived high cost of water. The metropolitan area expanded rapidly beyond the central area into higher elevations. Since the main water supplies were at the lower elevations, this meant water had to be pumped uphill and stored in reservoirs, to flow by gravity to customers. The fact that all customers pay the same rate no matter where they live is an advantage to those living in more distant and higher areas. The CAP is a system of canals, pumping stations and storage facilities that brings water 336 miles from the Colorado River at Lake Havasu east to the Phoenix area and then south to the Tucson area. Fourteen pumping plants lift water 2,400 feet in elevation to the terminus. The CAP idea preceded Arizona statehood. In the early years of the twentieth century some visionaries talked about bringing Colorado River water to central and southern Arizona. At the time this seemed infeasible. Meanwhile events were transpiring to make the vision a reality. In the 1920s, six of the seven Colorado River states agreed to divide the river water. Arizona was the sole dissenter and did not go along with the agreement for more than twelve years. Meanwhile Hoover Dam was built in the 1930s, along with other Colorado River projects. When a large aqueduct was built to supply southern California with Colorado River water in the 1940s, Arizonans took notice and began lobbying for their own project. By 1960, all major Arizona politicians and political interests were behind the project. Congress approved CAP in 1968. The original project included dams on the upper Gila River in New Mexico, the middle Gila River in Arizona, the San Pedro River, and the Verde River at Fort McDowell. Ultimately none of these dams was built. Instead changes were made to some existing dams, and a new

dam was added along the Agua Fria River. Construction began. President Carter expressed doubts about the project-building approach to solving western water problems, and demanded changes in Arizona water laws to promote conservation. The Arizona Legislature responded to the threatened loss of CAP funding by passing the Groundwater Management Act of 1980. A three-county water district was formed to manage the project after completion and to develop water subcontracts with cities, farms, mines and other prospective users.

Completed to Tucson by 1990, the project faced problems. Few farms or mines signed CAP contracts, not even those that once enthusiastically supported the concept. Farmers found the cost too high and the supply too unreliable. The mines were concerned that the quality of the water would affect their mining processes. The cost of extending pipelines to individual farms and mines also was a significant factor. The City of Tucson was virtually the only commercial customer for CAP in Pima County, although water was allocated to the Tohono O’odham through a legal settlement. Since Tucson Water has by far the largest municipal CAP contract, its customers, by supporting CAP, pay the majority of the costs to augment the water supply. Farms, mines and water companies meanwhile can continue to pump groundwater at a relatively low cost. Many people believed that other water users in the basin should be required to use CAP water and/or to share the costs of those switching to renewable supplies. Arizona law, however, has no provisions to enforce such a requirement. To many people, however, CAP water represented a long-awaited water source to benefit the Tucson area. With CAP on-line, less groundwater would be pumped. CAP’s Colorado River water, however, differed from the groundwater to which most people in the area were accustomed. CAP water is harder and contains more total dissolved solids than local groundwater. Despite this situation officials believed that citizens would find the new water source to be acceptable. As the CAP canal neared completion in 1989, the Tucson City Council adopted the Tucson Water Resources Plan for the 110-year period, 1990-2100. It called for an aggressive phase-in of direct use of CAP water, combined with recharge and recovery of excess CAP water in early years, recovery of recharge credits, reuse of effluent and some continued use of groundwater. There was a heavy media campaign surrounding the introduction of CAP water, including a well publicized taste-test, TV and radio ads, and direct-mail fliers. The only substantive warnings about water quality were directed at kidney dialysis patients, those on restricted salt diets, and aquarium owners. In general, the introduction of CAP water was expected to go smoothly. Starting in November 1992, CAP water was delivered to approximately 84,000 customers, or about 58 percent of the connections in the Tucson Water service area. Problems were soon reported by some customers. Many people complained of red, brown or yellow-colored water coming from their taps. Some reported broken pipes, damage to water-using appliances such as water heaters or evaporative coolers, skin rashes, and even dead fish in aquariums and damage to pools.

|