| |

Introduction

| Diverse

cropping practices and weed management | Conclusion

| References

Introduction

Farmers must continuously deal with

weeds in crops and their importance is reflected in the amount of manual

labor, tillage, and herbicides used for their control. Herbicides are

typically 20 to 30% of input costs in North American cropping systems. In

Canada, over 80% of total pesticide sales are herbicides and they account

for approximately $1.1 billion in annual sales.

Successful weed

management will require a shift away from simply controlling problem weeds

to systems that prevent weed reproduction, reduce weed emergence, and

minimize weed competition with crops. This paper will explore the merits

of diverse cropping practices in terms of managing weeds in a

cost-effective and environmentally sustainable manner.

Diverse Cropping Practices and Weed

Management

Crop rotations

Changes in weed

populations are the result of selection pressures imposed by agronomic

practices in conjunction with the modifying effects of the prevailing

environmental conditions. Weed density data from 56 site-years of western

Canadian studies indicated that the overall ranking of effects on weed

populations was climate > crop rotation > tillage (Blackshaw et al.

2003). This indicates that crop rotation is indeed one of the most

important factors that farmers can alter to better manage their weed

infestations. Indeed, a summary of rotation studies found that weed

densities in rotation were less than in monoculture in 19 of 25

cases.

Monoculture cropping facilitates an increase in weed species

that are able to effectively compete with that crop or that overcome

competition through some avoidance mechanism. A long-term rotation study

that compared continuous winter wheat production with winter wheat grown

in rotation with canola, flax, or fallow found that the major difference

in weed populations was between monoculture winter wheat and the more

diverse rotations (Blackshaw et al. 2001a). Mean weed densities in May in

the winter wheat phase of the rotation were 49 plants m-2 in continuous

winter wheat but less than 10 plants m-2 in the other

rotations.

Crop diversification provides more control opportunities

and disrupts the life cycle of weeds and thus their reproductive

potential. Crop rotations including cereal, oilseed, and pulse crops allow

for greater herbicide choice over years. Annual and perennial forages,

especially when grown in rotation with annual grain crops, can be an

effective strategy to reduce weed populations. Different crops are

naturally planted at different times of the year and this can

significantly affect weed populations. Systematically changing planting

dates and crop species prevents any one weed species from developing into

a major problem (Derksen et al. 2002).

Cover crops, green

manures and silage crops

The use of cover crops and their residues

has the potential to reduce pests including weeds through competition,

physical suppression and allelopathic effects. Winter rye can be a useful

cover crop to suppress weeds in fall and early spring. Undersown biennial

sweetclover effectively reduced weed establishment after harvest and in

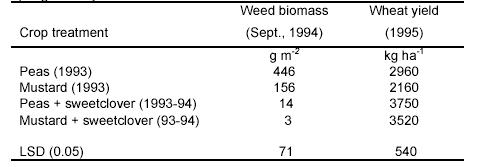

early spring and its decaying residues provided excellent weed control

throughout the remaining portion of the fallow year (Table 1). Higher

wheat yields the following year were due to much lower weed populations

and to nitrogen fixation by sweetclover. The use of green manure and cover

crops such as sweetclover, red clover, and fall rye for weed management

has been widely adopted by organic farmers on the Canadian Prairies but

their use also has good potential in conventional farming systems.

Table 1. Effect of undersown sweetclover in 1993 on weed

growth during fallow in 1994 and spring wheat yield in 1995.

Harker et al. (2003b) demonstrated that early cut cereal silage

effectively lowers weed populations by terminating weed growth before

viable seed production and thus weed seedbanks were reduced over time.

Intercropping and underseeding

A three-year study

conducted at two locations in Alberta found that intercropping has

potential as a weed management tool. Weed biomass in a barley-canola

mixture was less than in monocultures of either crop (Table 2). Weed

biomass in a barley-pea mixture was similar to monoculture barley but much

less than in monoculture peas.

Table 2. Weed biomass response to

monocultures of barley, canola, and peas and various mixtures of these

crops.

.jpg)

Underseeded forages in annual crops add diversity to

cropping systems. They contribute to weed suppression and can be harvested

as hay or grazed directly by livestock. Livestock consume many weeds when

grazing and thus contribute to diversified weed control.

Crop

species, cultivars, seed rates and row spacing

Crop species and

crop cultivars vary considerably in their competitive ability with weeds.

Increased competitive ability of crops has been associated with early

emergence, rapid leaf expansion forming a dense canopy, increased plant

height, early vigorous root growth, and increased root size.

Spring wheat cultivars that were taller and tillered more

profusely caused the greatest reductions in seed production of the

simulated weeds oat and mustard (Hucl 1998). These wheat cultivars also

yielded 25 to 30% more than the less competitive cultivars in the presence

of competing species. There are theories that ‘competitive’ cultivars may

yield less under weed-free conditions as they may put more resources into

vegetative growth at the expense of grain production. However, Results of

this study did not support that concept. A Danish study similarly reported

that there was no correlation between competitiveness with weeds and yield

potential of seven barley cultivars. This has important implications for

plant breeders; they need not sacrifice yield potential when selecting for

competitive genotypes.

Hybrid cultivars have been widely developed

to increase yield of some crops but competitive ability with weeds may

also be improved. Early vigor is often greater in hybrid than in

open-pollinated canola cultivars and these hybrid cultivars have been

shown to be more competitive with weeds (Harker et al. 2003a).

The

establishment of a crop with a more uniform and dense plant distribution

can increase its ability to suppress weeds. This is due to more rapid

canopy closure that better shades weeds and to better root distribution

that improves access to soil nutrients and water. A study where treatments

were applied in four consecutive years found that an increase in spring

wheat seed rate from 50 to 300 kg ha-1 reduced stork’s-bill (Erodium

cicutarium (L.) L’Her. ex Ait.) biomass by 53 to 95% and increased

wheat yield by 56 to 498%. Additionally, stork’s-bill in the soil seedbank

for future weed infestations was reduced by 79% (Figure 1). The greatest

weed suppression may occur when higher seed rates were combined with

planting of large wheat seed.

.jpg)

Figure 1. Effect of increasing wheat

seed rates on stork’s-bill (redstem filaree) seed in the soil seedbank at

the Conclusion of a four-year study.

Some of the greatest

agronomic benefits are realized when crops are grown both in narrow rows

and at higher densities. Blackshaw et al. (2000a) documented lower weed

biomass and greater dry bean yields when row spacing was decreased from 69

to 23 cm and when dry bean density was simultaneously increased from 20 to

50 plants m-2.

Tillage diversity

As farmers have adopted zero tillage there

have been concurrent increases in numbers of certain weed species such as

foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum L.) and dandelion (Taxacum

officinale Weber in Wiggers). Periodic wide-blade tillage within a

zero-till system has been shown to effectively control foxtail barley

(Blackshaw et al. 2000b). Tillage diversity is not something that most

farmers consider but it may have merit in some situations.

Conclusion

Diverse

cropping systems have many advantages in terms of increased soil health,

decreased pest pressure, and more stable and potentially higher net

returns. In terms of weeds, diverse cropping systems prevent any one or

two weed species from becoming major weed problems and can result in

reduced weed densities over time. Diverse cropping systems not only

include various cereal, oilseed, pulse, and forage crops in rotation but

also make use of intercropping, green manure or cover crops, and silage or

hay production. Weed management can be further improved by growing

competitive crop cultivars, using higher seed rates of good quality seed,

planting in narrow rows, and alternating between spring-and winter-sown

crops. Adoption of diverse cropping systems is required to ensure the

economic and environmental health of future farming operations.

References

- Blackshaw, R.E., Larney, F.J., Lindwall, C.W., Watson, P.R., and

Derksen, D.A. 2001a. Tillage intensity and crop rotation affect weed

community dynamics in a winter wheat cropping system. Can. J. Plant Sci.

81:805-813.

- Blackshaw, R.E., Molnar, L.J., Muendel, H.-H. Saindon, G., and Li,

X. 2000a. Integration of cropping practices and herbicides improves weed

management in dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Weed Technol.

14:327-336.

- Blackshaw, R.E., G. Semach, G., Li, X., O’Donovan, J.T. and Harker,

K.N. 2000b. Tillage, fertiliser and glyphosate timing effects on foxtail

barley (Hordeum jubatum) management in wheat. Can. J. Plant Sci.

80:655-660.

- Blackshaw, R.E., Thomas, A.G., Derksen, D.A., Moyer, J.R., Watson,

P.R., Legere, A., and Turnbull, G.C. 2003. Examining tillage and crop

rotation effects on weed populations on the Canadian prairies. In

Kohli, R.K. and Singh, H.P., eds. Handbook of Sustainable Weed

Management, Haworth Press, Binghampton, NY. (In press)

- Derksen, D.A., Anderson, R.L., Blackshaw, R.E., and Maxwell, B.

2002. Weed dynamics and management strategies for cropping systems in

the northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 94:174-185.

- Harker, K.N., Clayton, G.W., Blackshaw, R.E., O’Donovan, J.T., and

Stevenson, F.C. 2003a. Seeding rate, herbicide timing and competitive

hybrids contribute to integrated weed management in canola (Brassica

napus). Can. J. Plant Sci. 83:433-440.

- Harker, K.N., Kirkland, K.J., Baron, V.S., and Clayton, G.W. 2003b.

Early-harvest barley (Hordeum vulgare) silage reduces wild oat

(Avena fatua) densities under zero tillage. Weed Technol.

17:102-110.

- Hucl, P. 1998. Response to weed control by four spring wheat

genotypes differing in competitive ability. Can. J. Plant Sci.

78:171-173.

R.E. Blackshaw1, J. R. Moyer1,

J. T. O’Donovan2, K. N. Harker3, and G. W.

Clayton3

1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Box 3000, Lethbridge, AB T1J

4B1

2Agriculture and

Agri-Food Canada, Box 29, Beaverlodge, AB T0H 0C0

3Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 6000

C&E Trail, Lacombe, AB T4L 1W1 |

|