![]()

Table of Contents

![]() Potential

Human Health and Environmental Hazards

Potential

Human Health and Environmental Hazards

![]() Methods

to Reduce Waste Contamination

Methods

to Reduce Waste Contamination

![]() Virginia

State Regulations for Swine Production

Virginia

State Regulations for Swine Production

![]()

Raising a large quantity of swine creates an overwhelming quantity of manure. To control the accumulation of the waste in the swine confinement area, a waste disposal facility is needed. To dispose of the waste in the swine pens, the area is flushed with water through slatted floor systems. Depending on the size of the swine confinement facility, the confinement area may be flushed many times during daily operation. The wastewater is channeled into gutters and flushed into a solid manure separator. The separator separates the solid manure from the wastewater. The solid manure is collected and is used for compost, nursery mulch, and animal feed supplements. After the solids are separated, the wastewater or slurry is pumped into a lagoon. Once in the lagoon, anaerobic microorganisms degrade the slurry. Organic nitrogen in the waste is converted to ammonia and ammonium. Compounds consisting of carbon are decomposed into carbon dioxide and methane. In order to allow the waste to degrade, the typical retention time in a waste lagoon is from 6 to 24 months.

The lagoon effluent can also be used as a commercial fertilizer. In most large operations, the lagoon effluent is pumped directly into irrigation systems and is distributed to crops and fields.

![]()

Potential Human Health and Environmental Hazards

Impounding swine waste and using it for agricultural fertilizer can impose possible human health and environmental hazards. Currently, Virginia regulations require the waste lagoon to be lined with a compacted clay liner covered with a geomembrane. However, many older lagoons were constructed without compacted clay or geosynthetic liners. Consequently, the large amounts of seepage from the lagoons can infiltrate into the groundwater. In addition, if the distribution of waste onto fields is not properly managed, this too can cause human health hazards. These hazards arise from high levels of nitrate nitrogen in the soil and groundwater. Nitrate nitrogen is a naturally occurring compound in the soil. Plants absorb the nitrogen and other nutrients to survive. Animals consume the plants but cannot use all of the nitrogen present in the plants. Swine excrete 40 to 60 percent of the nitrogen they consume in both urine and fecal matter. If the application of the lagoon effluent is not managed properly and too much is applied to fields, the nitrate nitrogen content of the soil and ground water can rise to unacceptable levels (10 PPM as N). High nitrate nitrogen levels in groundwater can cause two serious problems, eutrophication and methemoglobinemia.

Eutrophication is the process in which high levels of nitrogen cause

massive growth of algae in streams or lakes. Which, in turn, the algae consume

almost all of the oxygen present in the water. The absence of oxygen in the

water causes the fish and other aquatic life to die by asphyxiation.

Eutrophication is the process in which high levels of nitrogen cause

massive growth of algae in streams or lakes. Which, in turn, the algae consume

almost all of the oxygen present in the water. The absence of oxygen in the

water causes the fish and other aquatic life to die by asphyxiation.

Methemoglobinemia, or Blue Baby Syndrome affects humans, particularly children, who consume nitrogen contaminated water. Nitrate Nitrogen affects the body's ability to transport oxygen, causing slow asphyxiation. This condition can be fatal in infants.

Nitrate nitrogen in lakes and streams may only be a temporary pollution problem. However, nitrate nitrogen present in the groundwater may unfortunately be a permanent problem if no precautions are taken to prevent pollution..

![]()

Methods to Reduce Contamination of Groundwater

Waste Management programs

Many states, including Virginia, require that swine producers have a certified waste management plan. This waste management plan must include details for the storage, distribution, location of distribution, and rates of application of the waste as well as the periods during the year when the waste is applied.

These management plans should allow the proper distribution of the waste that is both beneficial to the swine producers, the community, and the environment.

Riparian Buffers

Some of the potentially harmful nitrate nitrogen present in the soil and groundwater by spreading swine waste can be prevented from entering water sources by using riparian buffers. Riparian buffers are zones of trees or vegetation which will prevent most of the nitrate nitrogen present in the groundwater from reaching surface waters, such as lakes or streams. The plants and trees that compose a riparian buffer will consume some of the nitrogen present in the groundwater. Bacteria, which live in the wet soil near streams and lakes, consume the dead roots of the vegetation and denitrify the nitrate nitrogen in the groundwater.

However, without a proper waste management plan, riparian buffers can become overwhelmed and become ineffective to remove significant amounts of nitrate nitrogen from the soil within the root zone. If the buffers become overwhelmed, the nitrate nitrogen is allowed to pass through the root zone and into the groundwater table.

![]()

Virginia State Regulations for Swine Production

In order to preserve the groundwater quality and to protect the public, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has put forth a set of regulations for the impoundment and monitoring of swine waste.

Size of Operation

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) is the governing body over swine production and waste disposal facilities. The DEQ makes two distinctions for obtaining a permit, operations with less than 750 swine and operations with 750 swine or more weighing over 55 pounds.

The DEQ designates swine operations containing less than 750 swine as "concentrated or intensified" and are subject to the Virginia Pollution Abatement permit program. The designation is determined by individual inspection of the facility.

For operations with 750 swine or more weighing over 55 pounds, A 10-year general permit for confined animal operations can be obtained through the DEQ.

Storage Capacity

The waste impoundment facility must be designed to prevent discharge of waste and maintain one foot of freeboard except in cases greater than the 25-year, 24-hour storm. The impoundment facility must also provide adequate capacity to accommodate periods when land distribution of waste is not possible.

Liner Specifications

Newly constructed impoundment facilities must possess a liner certified by a manufacturer or professional engineer. A 60-mil HDPE liner passing Tear Resistance Tests (ASTM D 1004), Puncture Resistance Tests (FTMS 101C), Environmental Stress Crack Tests (ASTM D 1693), Ultaviolet Resistance Tests (ASTM D 3334), and Chemical Resistance Tests (USEPA Test Method 9090) should be used. (Sharma and Lewis, 1994)

Flooding

The waste impoundment facility cannot be located in a 100-year flood plain unless protected from floodwater.

Buffers

For all operations residing under general permit, the following buffer zones apply:

Monitoring

For all operations residing under general permit, the following conditions apply:

![]()

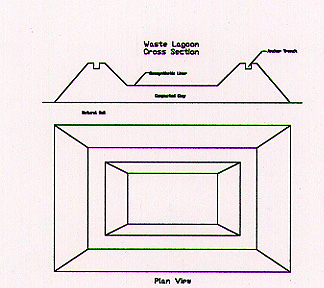

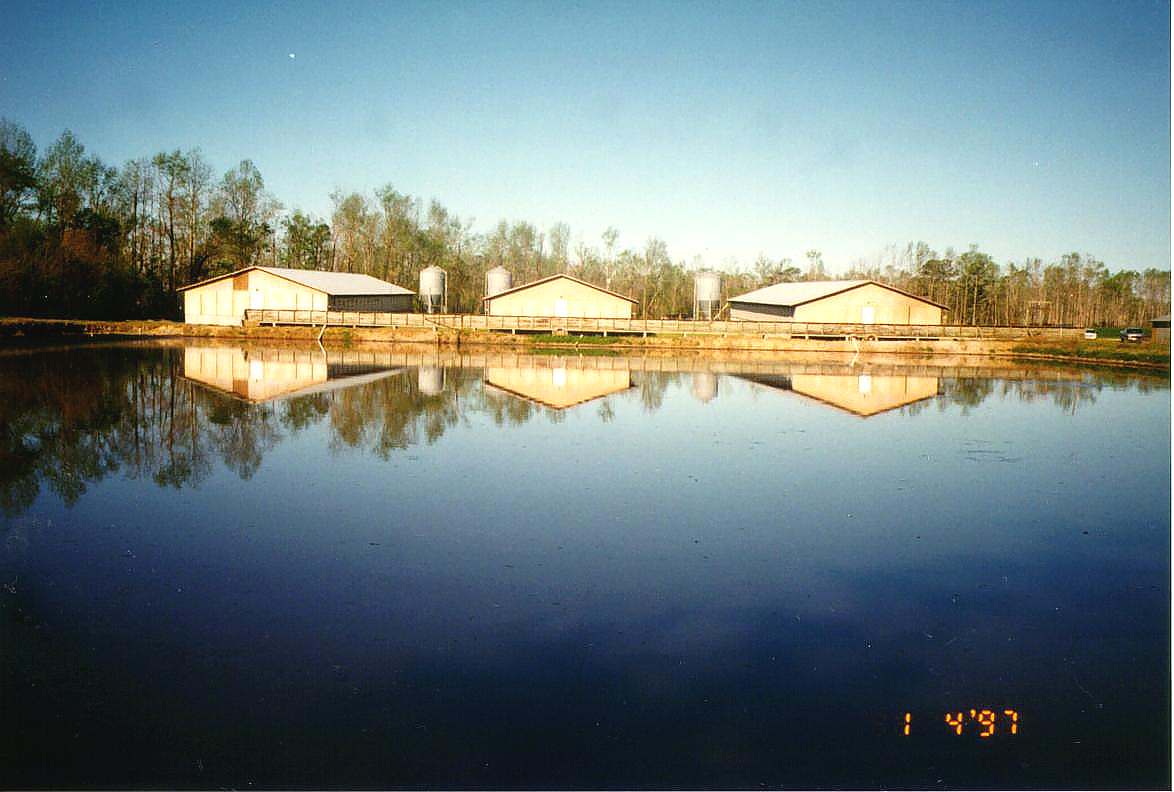

Here are some photos of swine waste lagoons. The top picture is a plan view and a cross-section of a typical above ground lagoon. The third photo is actually an unlined earthen pit. An unlined earthen pit is for short term storage and can leach high concentrations of pollutants into the groundwater. Photos are courtesy of Dr. Diana Rashash.

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]() NCSU Swine Extension Most informative

link on the subject!

NCSU Swine Extension Most informative

link on the subject!

![]() NCSU Animal

and Poultry Waste Management Center

NCSU Animal

and Poultry Waste Management Center

![]() Virginia Department of Environmental

Quality

Virginia Department of Environmental

Quality

![]() Swine Resources at the

Livestock Virtual Library

Swine Resources at the

Livestock Virtual Library

![]()

References

Sharma, H.D. and S. Lewis (1994) Waste Containment Systems, Waste Stabilization, and Landfills: Design and Evaluation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York.

NCSU (1995) "Water Quality and the North Carolina Swine Industry." http://www2.ncsu.edu/unity/project/www/ncsu/cals/waste_mgt/

Sutton et al. (1995) "Managing Nitrogen in Swine Manure for efficient Corn Production." Purdue Swine Day Reports.

![]()

|

|

Student authors: Joe Woliver

Faculty Advisor: Daniel Gallagher, dang@vt.edu

Copyright © 1998 Daniel

Gallagher

Last Modified: June 7, 1998