Mercury

in Their Midst

When released into

the environment in substantial amounts over a period of time, mercury is a

well-documented killer, not only of wildlife but of people as well.

The raw element

itself, still called quicksilver by some, is the only common metal found

in nature that’s liquid at ordinary temperatures. Humans have found

hundreds of uses for it, from making medicines to the manufacture of other

products ranging from pesticides to paints, thermometers to hats. The

phrase “mad as a hatter” comes from centuries past, when mercury

was used in the manufacture of felt hats. A common byproduct was mentally

and physically impaired workers, hapless victims of acute mercury

poisoning.

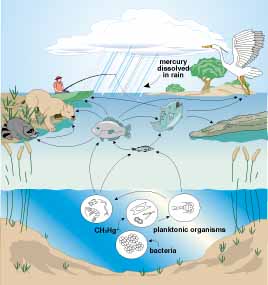

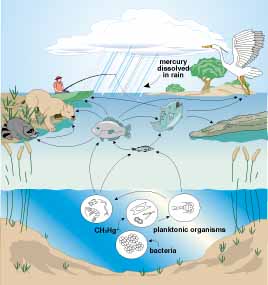

Mercury’s

pathway into Everglades wildlife primarily begins in the

skies, with mercury-loaded rainfall. Sulfate-reducing bacteria,

mainly living in sediments and in mats of floating algae, absorb

rainwater mercury and turn it into its organic form, methylmercury

(CH3Hg+). Microorganisms which eat such

bacteria feed successive populations of larger organisms in the food

web. At each step, methylmercury levels get concentrated. For

wetland-dependent animals such as wading birds, raccoons and some

panthers, concentrations can reach dangerously high levels. (BRUCE

HALL ILLUSTRATION) |

Like most elements,

mercury is something of a chameleon, able to assume many forms. In the

environment, the most toxic form is methylmercury, a tasteless, colorless

and odorless compound that readily enters the food chain. Once in the

tissues of organisms, methylmercury has a strong tendency to stay put.

Over time, the compound can build up to dangerous levels in fish,

shellfish and other aquatic life. People and wildlife with heavy diets of

such tainted foods can accumulate the poison as well and suffer crippling,

even lethal consequences.

In the digestive

tract, methylmercury gets rapidly absorbed and can invade all tissues,

including the brain and the wombs of pregnant women. In high enough

concentrations, the neurotoxin can cause irreversable brain and nerve

damage, seizures, kidney failure, even blindness.

Of all the abuses

of mercury by manufacturers this century, by far the worst occurred in

Japan, in the vicinity of a small fishing village on the island of Kyushu.

Between 1953 and 1960, the Chisso Chemical Company dumped mercury-loaded

sludge into Minimata Bay, where it accumulated in fish and shellfish. The

pollution killed fish, seabirds, housecats--and reportedly as many as 700

inhabitants of the bayshore village. Hundreds more were crippled,

including scores of babies born with horrific birth defects.

Nothing so terrible

has happened in the U.S., although there have been numerous instances of

methylmercury poisoning. The first example to draw significant public

attention was in 1969, when some children in New Mexico got sick from

eating hog meat from animals fed mercury-treated feed grain.

As it happens,

indigenous peoples tend to eat lots of fish, which too often puts them at

risk for mercury poisoning. Miners in Brazil use tons of mercury each year

in a process for gleaning gold dust from rivers near Manaus. In the early

1990s, health officials found downstream forest peoples with methylmercury

in their systems at levels up to four times a World Health Organization

safety standard.

In 1983, Pomo

Indians in California had to stop eating so many local fish because of

high mercury in the fillets. Two bands of Indians in Ontario, Canada were

awarded an $18.6 million settlement in a 1986 lawsuit against a paper mill

that had poisoned a river that gave the Indians their livelihood.

Mercury-loaded fish from the river sickened dozens of tribe members, and

resulted in the birth of several infants with severe mental and physical

defects.

Chippewa Indians in

Wisconsin in 1990 were found to have blood levels of mercury high enough

to cause developmental problems in fetuses. The Chippewas had a fondness

for the walleye that swam in local lakes.

In Florida,

Miccosukees and Seminoles are obliged to deal with a mercury contamination

problem that defies belief. Their tribal lands are virtually synonymous

with much of the Everglades, one of the largest tracts of unsullied

wilderness left in the world--with one exception. Although statistics aren’t

clear on the point, the Everglades may have the highest levels of mercury

contamination ever seen in a freshwater ecosystem, period.

Most Everglades

fish, turtles, alligators, wading birds, raccoons and even some insects

carry mercury burdens way above normal. The average concentration of

methylmercury in a fillet of an Everglades largemouth bass is 1.5 parts

per million (ppm), three times what the state’s Department of Health

calls safe.

To many Everglades

Indians, the mercury problem is just one more insult to their environment

they must deal with, says Joe Quetone, director of the Gov. Lawton Chiles’

Council on Indian Affairs. The tribes already are battling exotic species

of fish and other wildlife, saltwater intrusion and pollution from

agribusiness. “They’ve just added mercury to the list,”

Quetone said.

Still, some tribal

leaders are fully resentful of how the ‘Glades mercury issue has been

handled by state authorities and have balked at what they call being “singled

out” by health officials for mercury testing. So far, no evidence has

surfaced that indicates a health problem tied to mercury among any of the

Everglades’ human inhabitants.

But that may be

because many Indians don’t eat fish anymore, said one Miccosukee

woman living in Big Cypress. “Nobody eats these fish around here,”

she said. “When we want fish, we do like everybody else--we go to

Publix.” --F.S.

Reposted with permission of Frank Stephenson, editor of FSU

Research in Review.

6/8/98